A nostalgic journey into Eastleigh's 90s manyanga matatu culture

The matatus were pimped, with colourful names inspired by urban culture, inside lights, graffiti vinyl sticking and painting, and strong sound systems.

I grew up on Wood Street in Eastleigh during the 1980s. Apart from the Kenya Bus, which had a garage where Yare Mall now sits, the Rosa or Coaster minibuses were the main public transport vehicles in Eastleigh at the time. DC American Flag, Yeke Yeke, Yellowman, Red Sea, and Kichuna are some of the Rosa minibuses that I recall. They were ordinary public service vehicles with limited artistic inventiveness and sound.

Then came the 1990s, which coincided with our teenagehood and marked an era of hip-hop culture from the streets of New York to Nairobi. Eastleigh (route No.9/6) pioneered the manyanga urban subculture. These matatus were pimped, with colourful names inspired by urban culture, comfortable and puffy seats, inside lights, graffiti vinyl sticking and painting, and strong sound systems.

More To Read

- Matatu industry players calls for urgent government reforms to end lawlessness on roads

- Matatu operators, hawkers ordered to vacate Nairobi CBD stages and streets at night for cleaning

- Court allows DCI to detain six men suspected of robbing passengers in Nairobi

- Nairobi’s matatu madness persists as City Hall’s attempts to offer solution fall flat

- Eastleigh businesses staring at losses from uncovered risks as many shun insurance

- Untold stories of Somali culture through pictures and art

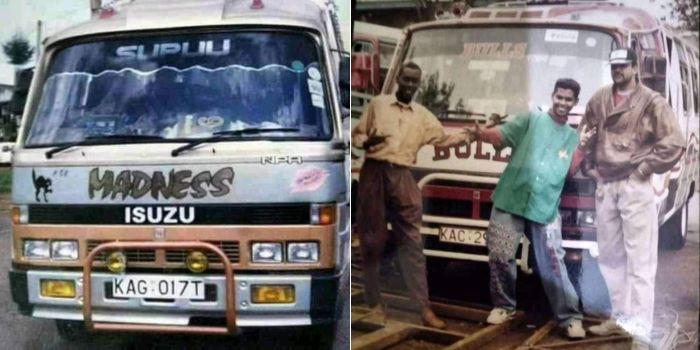

Driver Kifie and conductor Punky Boy, of route no. matatu, Rainbow. (Photo: Handout)

Driver Kifie and conductor Punky Boy, of route no. matatu, Rainbow. (Photo: Handout)

This was a new era in public transport and Eastleigh route number 9 gave Buru Buru 58, South B, Outering and Kangemi a run for their money. “Easich” as it was fondly known was among the trendiest and coolest neighbourhoods in Nairobi in the 90s.

"It was an era in Eastleigh when you were either connected to a matatu or knew someone who worked in the matatu business. Matatus' members wielded considerable power. We called the shots," says Hassan Rasta, a matatu arts pioneer in Nairobi known for pimping matatus in the 1990s.

“I worked for several manyangas so I remember the matatu culture back then. One of the meeting places for conductors was at Samburu Electronics on the twelfth. I would be paid like Sh80 for a whole day. But we loved the fame and celebrity status that being a matatu crew meant,” Clive Wanguthi Dades said admitting that the crew life was also shrouded with controversy of alleged promiscuity that came with the fame.

“We would simply pay Sh5 for the circuit. Off-peak was Sh3. Matatus would be packed with students from St Theresa's, Ngara Girls, Eastleigh High, Pumwani, and Jamhuri after school.

Baby Coach which was my first Manyanga ride remained a favourite throughout the 90s but the competition was tight from the following matatus; Pirates Coach, Purple Rain Wrecks & Effect, ABC, Bel Biv Devoe, ZamZam, Jiji Spoiler, Korrect, Trick Tuck, Golf Club, Toronto Blue Jays, Sailor, Rainbow, Kappa, Heartbreaker, Chicago Bulls, White Sox, Orlando Magic, Total Madness, Naughty By Nature, Color Me Bad, Coolio, Funky Farm, Shy Guy, Biggie Train, Winner, Shaggy, peacock, jealousy, Fantasy, Delight, London Beat, Arafat, Mashallah, Shy Guy and Lydia.

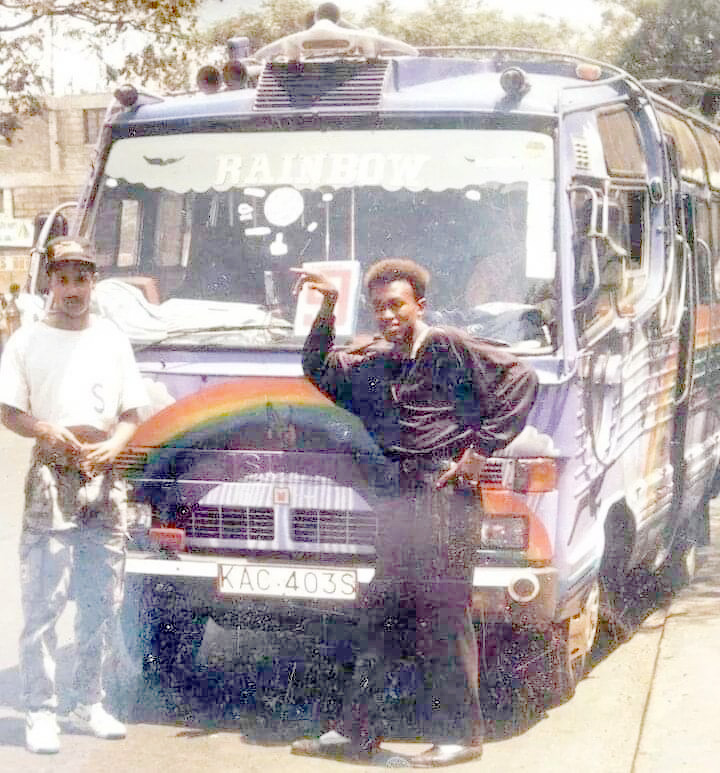

The conductors and drivers enjoyed an almost celebrity status and always wore the latest fashion trend of the 90s like baggy jeans, bandanas, baseball caps, "big shoes", sneakers and college jackets.

Blackie, Micky, Jimmy, Georgie Pojjy, Ridu, Kifle, Abrash, TZ, Franco, Vaite, Russom, Babafo, Hussein, Mgoso, Kaka Taz, Elias, Bernado, Remmy, Debarge, Saidi, Mawaya, King Barbara, Selle these conductors were Eastleigh's 90s celebrities.

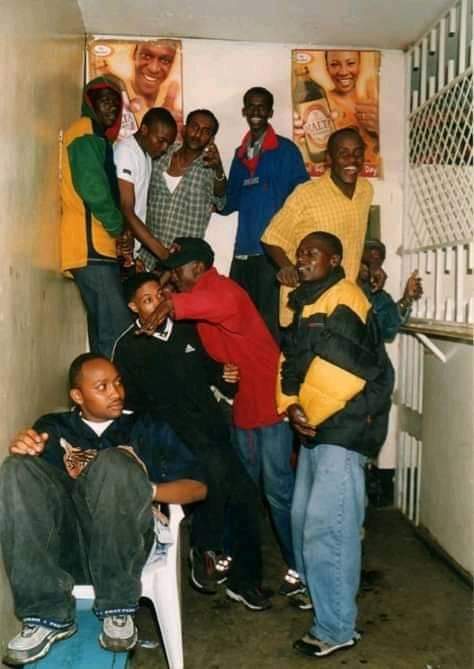

The Orlando Magic Shaq matatu crew of Kanji, Ridu, Blackie, and Selle, as pictured in 1992. (Photo: Handout)

The Orlando Magic Shaq matatu crew of Kanji, Ridu, Blackie, and Selle, as pictured in 1992. (Photo: Handout)

Sometimes we'd go a circuit just for the music," Lucy Kigotho recalls her high school years.

In that era, new Sheng words were coined around matatu culture, such as "Vako" and "Sare," both of which mean riding without paying the fare, "Nganya" (pimped matatu), Wang'ora (an old matatu), and "Battery ya Mathree," which was mostly a family member of the vehicle's owner who sat near the door with a gadget to ensure all passengers paid. "Chrome" (full) and Circuit, which was the route to and from Eastleigh town.

“After college, I was employed to do branding of sales vehicles like Hedex, Eveready, Nivea, Vaseline, and Kimbo, but later found it boring and switched to matatu art. My first matatu to paint was Red Scorpion; it opened the way for me and gigs started coming in. The era of Manyangas had just started and demand for my artistic talent went up since the competition between matatus was so high in Eastleigh. I recruited and trained many young artists who are the big names in the industry,” 58-year-old trained graphic designer Hassan Rasta, born and raised in Melawa and an alumnus of Eastleigh High School, told The Eastleigh Voice.

A combination picture of Nasib Abdul Malik Samburu, the matatu music sound system guru of the 1990s, and Hassan Rasta, the pioneer of Nairobi matatu graphics. (Photos: Handout)

A combination picture of Nasib Abdul Malik Samburu, the matatu music sound system guru of the 1990s, and Hassan Rasta, the pioneer of Nairobi matatu graphics. (Photos: Handout)

Nasib Abdul Malik popularly known as “Samburu” was the Godfather of the matatu sound systems in Nairobi in the nineties. He owned the famous Samburu Electronics along General Waruingi Road, where Madina Mall stands today.

"My shop was the primary provider of sounds and electronics for the Eastleigh 6 and 9 routes, as well as other routes in Nairobi. I used to import electronics from Dubai," recalls the 62-year-old Samburu, born and raised in California's Eastleigh.

Samburu’s first gig to fix sounds was on the popular 80s Rosa Coaster matatu christened Yellowman owned by Blackie Yellowman. He was a young man in his twenties who had just graduated from college.

“Blackie opened my eyes to starting the matatu sound business after I fixed his Rosa matatu and later his new Isuzu matatu. My interest and creativity started here and I became the pioneer in fixing matatu sound systems in Nairobi. I would later master the art as we transitioned from the simple sound system to a more advanced one in the Isuzu where I fixed the Pioneer speakers, amplifier, Cross-over equaliser, and base. I would buy speakers at the Lasonic shop in Westlands and resell them,” said Samburu.

A 1990s Eastleigh no.9 crew, made up of Madonna, Selle, Said Booster, Doncolion, Samburu, Blackie, Ali, and Chinku. (Photo: Handout)

A 1990s Eastleigh no.9 crew, made up of Madonna, Selle, Said Booster, Doncolion, Samburu, Blackie, Ali, and Chinku. (Photo: Handout)

Samburu's Electronics' renown in the thriving 1990s Manyanga matatu sector would give him enough money to purchase his fleet of matatus, including the popular Spring Love. He was chosen Eastleigh Matatu chairman for ten years, was a founding member of the Matatu Welfare Association alongside its chairman Dickson Mbugua, and vied for the Kamukunji parliamentary seat in 2002.

He recalls escaping to Mombasa after orchestrating a three-day nationwide matatu strike when President Daniel Moi publicly chastised him for allegedly instigating matatu owners.

“I was watching on the news saying there is an Ethiopian inciting matatu owners to go on strike. He thought like many that I was an Ethiopian since the majority of the Eastleigh matatu owners were Ethiopian. But our national strike was a success,” Samburu said.

No.9 matatu drivers and conductors at their "Lovito Love" meeting place on Sixth Street in Eastleigh, Nairobi. (Photo: Handout)

No.9 matatu drivers and conductors at their "Lovito Love" meeting place on Sixth Street in Eastleigh, Nairobi. (Photo: Handout)

Eritrean and Ethiopian investors played a huge role in Eastleighs’ matatu business in the 90s.

“Seventy per cent of the Eastleigh matatus were owned by Ethiopians and Eritreans. Most had fled their country as asylum seekers seeking relocation to a third country in the West. They realised that the appropriate investment that would sustain their stay in Nairobi without the need for complicated paperwork as they waited to be relocated to a third country would be the Matatu business. We also had a few Kikuyus and later a few Somalis in the business but most learnt from the success of Ethiopians,” said Samburu.

Hassan Rasta says most of the Eritreans had experience in mechanics back in their country were interested in public transport and were enterprising.

“They invested heavily in pimping the matatus and fixing the sound system. They were determined to control the competitive route. Most however would later migrate to North America and Europe,” said Hassan Rasta.

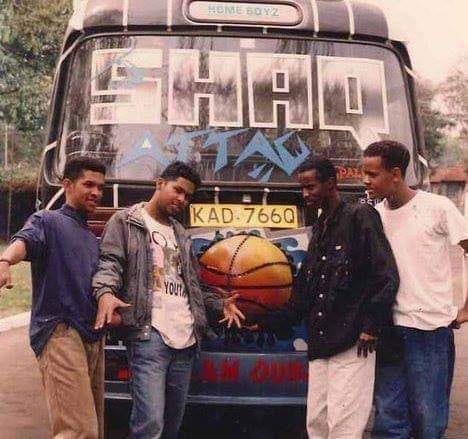

There have always been arguments over which manyanga had the best sounds. When I queried Samburu, he immediately recalled Total Madness and his cousin Khan's ownership of the Chicago Bulls.

A manyanga matatu known as "Total Madness", which arguably had the best sound system. (Photos: Handout)

A manyanga matatu known as "Total Madness", which arguably had the best sound system. (Photos: Handout)

What caused the manyanga matatu culture in Eastleigh to disappear?

“The reason why the manyanga culture died was the high demand for transport to Garissa Lodge and the expansion of Garissa Lodge. Many Kenyans had discovered the affordable shopping at Garissa Lodge leading to heavy traffic and an end to the circular route between Eastleigh and Town. Matatus could no longer do a circuit and had to turn back to Town near the General Waruingi road roundabout. Shoppers became the main passengers of the matatus. The demand to shop in Garissa meant passengers could no longer have the luxury to be choosy on the matatu to use and Wangoras slowly replaced the manyangas trademark of Eastleigh’s vibrant life in the 90s,” said Hassan Rasta.

Samburu blames the poor roads for the end of Eastleigh manyanga matatu culture.

“It became expensive to repair the manyangas because of the bad roads but later when the roads were paved it created a major traffic jam. While it took only 15 minutes to do a circuit it now took like an hour to beat the traffic,” Samburu said.

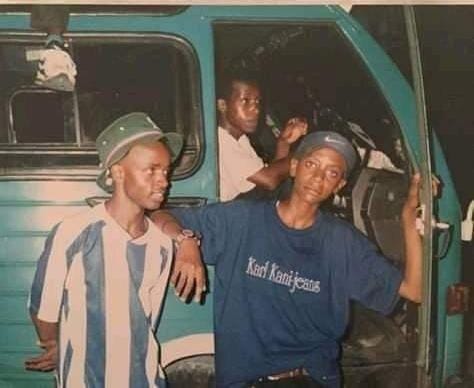

The Karl Kani matatu crew of Mugambi and Mickie in a 1992 picture. (Photo: Handout)

The Karl Kani matatu crew of Mugambi and Mickie in a 1992 picture. (Photo: Handout)

Samburu and a group of Eastleigh natives meet monthly to reminisce about the 1990s. They also have a Facebook group called Eastleigh My Childhood where one may revisit memories from Eastleigh's past.

"The memories will never fade for those of us who worked in the matatu business in the 1990s. We had a great experience. We were the pioneers of this urban subculture. We popularised Eastleigh," Samburu explained.

Before you go, how about joining our vibrant TikTok and YouTube communities for exciting video stories?

Top Stories Today